International centre for flourishing

What is the meaning of life? That was all – a simple question; one that tended to close in on one with years, the great revelation had never come. The great revelation perhaps never did come. Instead, there were little daily miracles, illuminations, matches struck unexpectedly in the dark; here was one.

-Virginia Woolf: To the Lighthouse (1927)

Like many great artists, Virginia Woolf wrestled with the big questions of life and provided often surprising insights on the complexity of existence. Although her question may sound simple, it is anything but. Searching for the meaning of life relates directly to existential questions of how best to conduct our lives to maximize the chance that we, other species and our tiny blue planet can flourish together. Over the course of human history, many have looked for answers to these deep questions, which arguably not only gave birth to art but also to philosophy and science. Sadly, finding the right answers is becoming more and more urgent in these difficult times of severe mental health problems, mass extinction and climate catastrophe.

A few decades ago, some of us began to use scientific methods to explore how the human brain creates deeply subjective states—including the underlying meaning-making processes that give us a sense of purpose and are fundamental to our flourishing. It has been an exciting journey, one that has already generated significant insights into the underlying brain mechanisms and networks for highly subjective phenomena, such as emotion and pleasure. These topics were traditionally considered outside the realm of science: Over the years some of our colleagues have repeatedly asked, “are you sure this is science?”

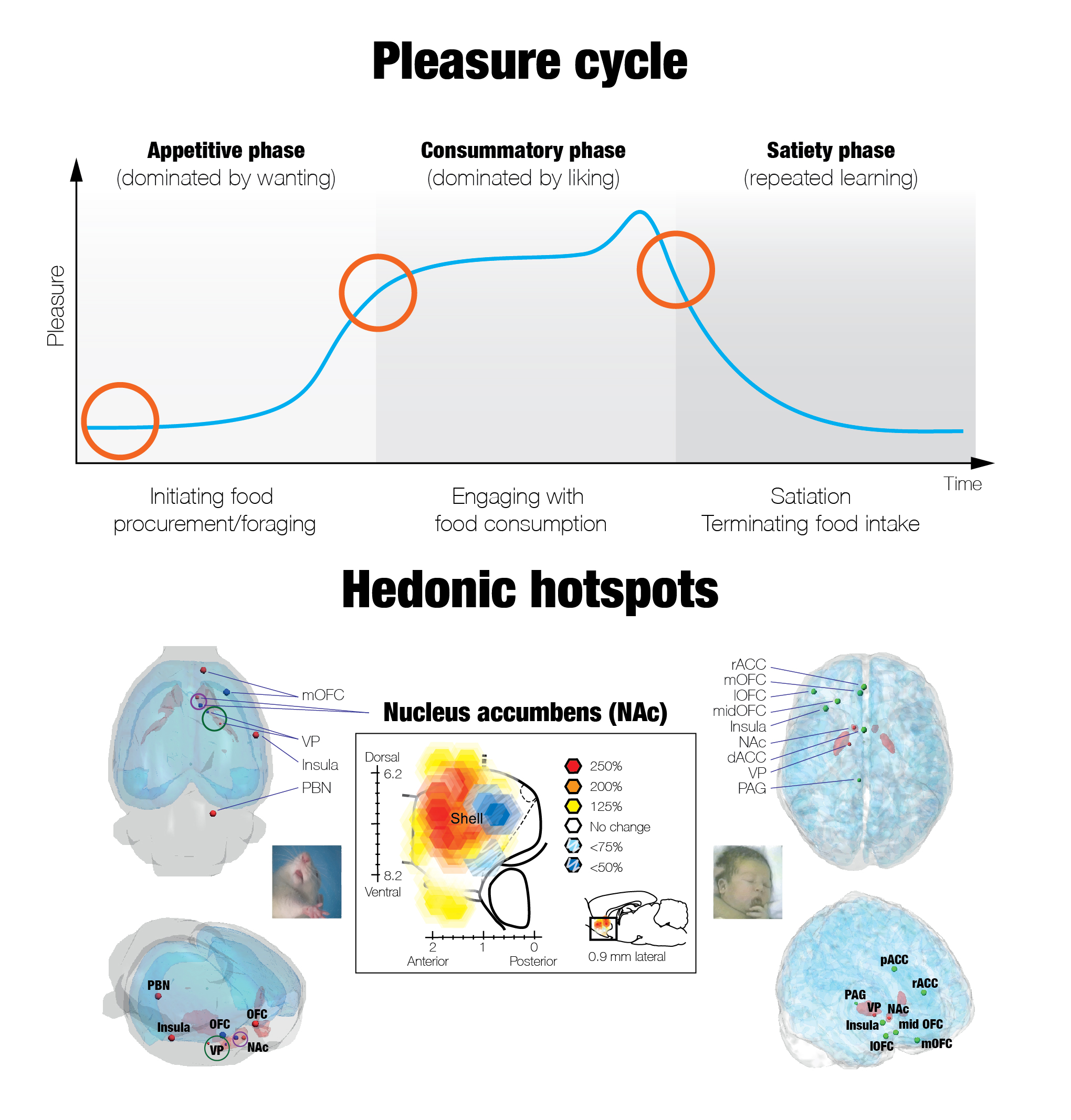

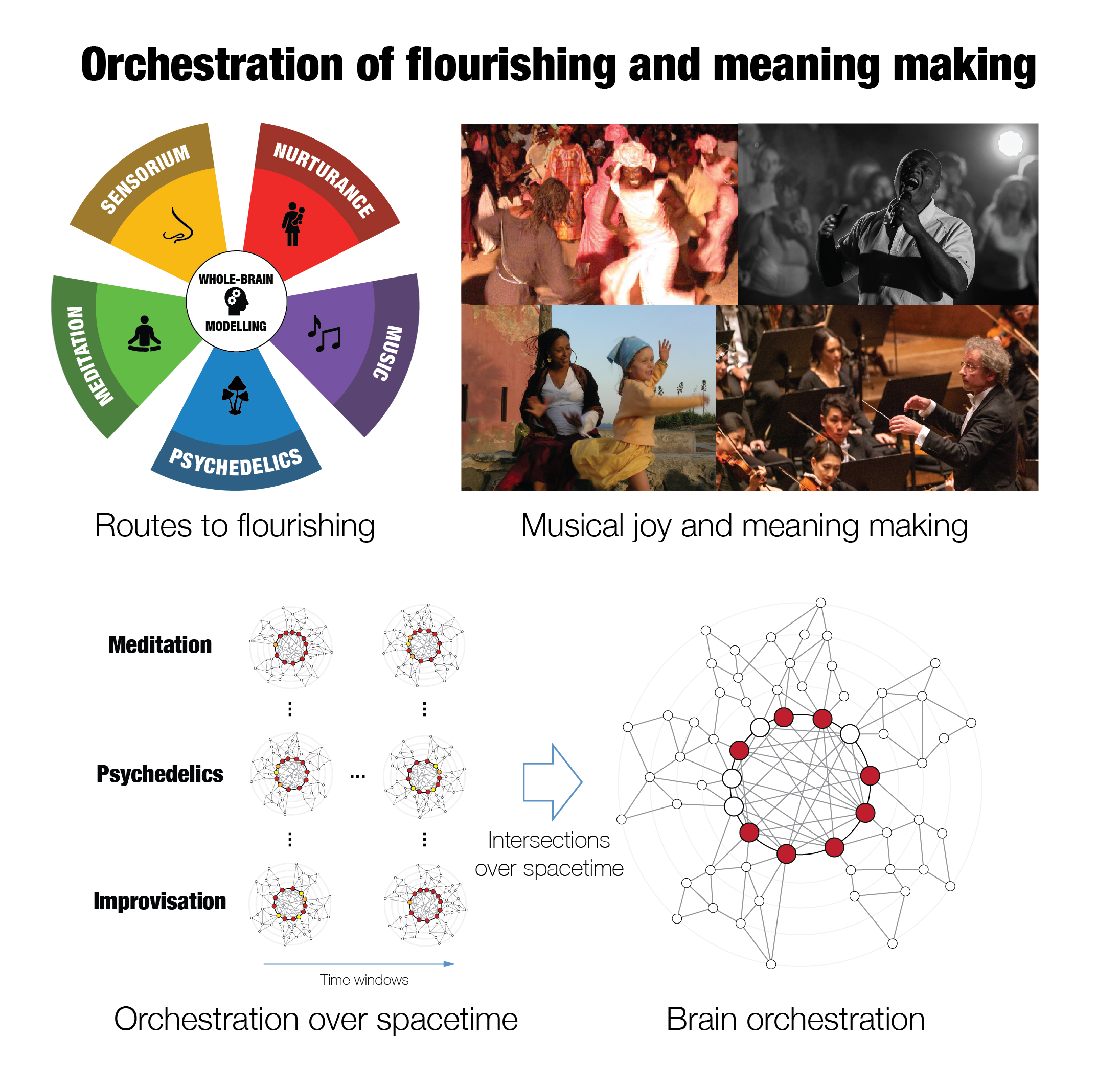

Refuting this scepticism, we reached back to Aristotle’s proposal that a meaningful life consists of both hedonia (pleasure, from ‘hedus’, the sweet taste of honey) and eudaimonia (a life well-lived, embedded in meaningful values). We created a neuroscience of hedonia by using indisputable sensory pleasures—food and sex—to investigate subjective brain states, such as emotion, pleasure and pain. These investigations have become increasingly interdisciplinary and more subtle, combining science with disciplines like music, which can evoke strong emotions.

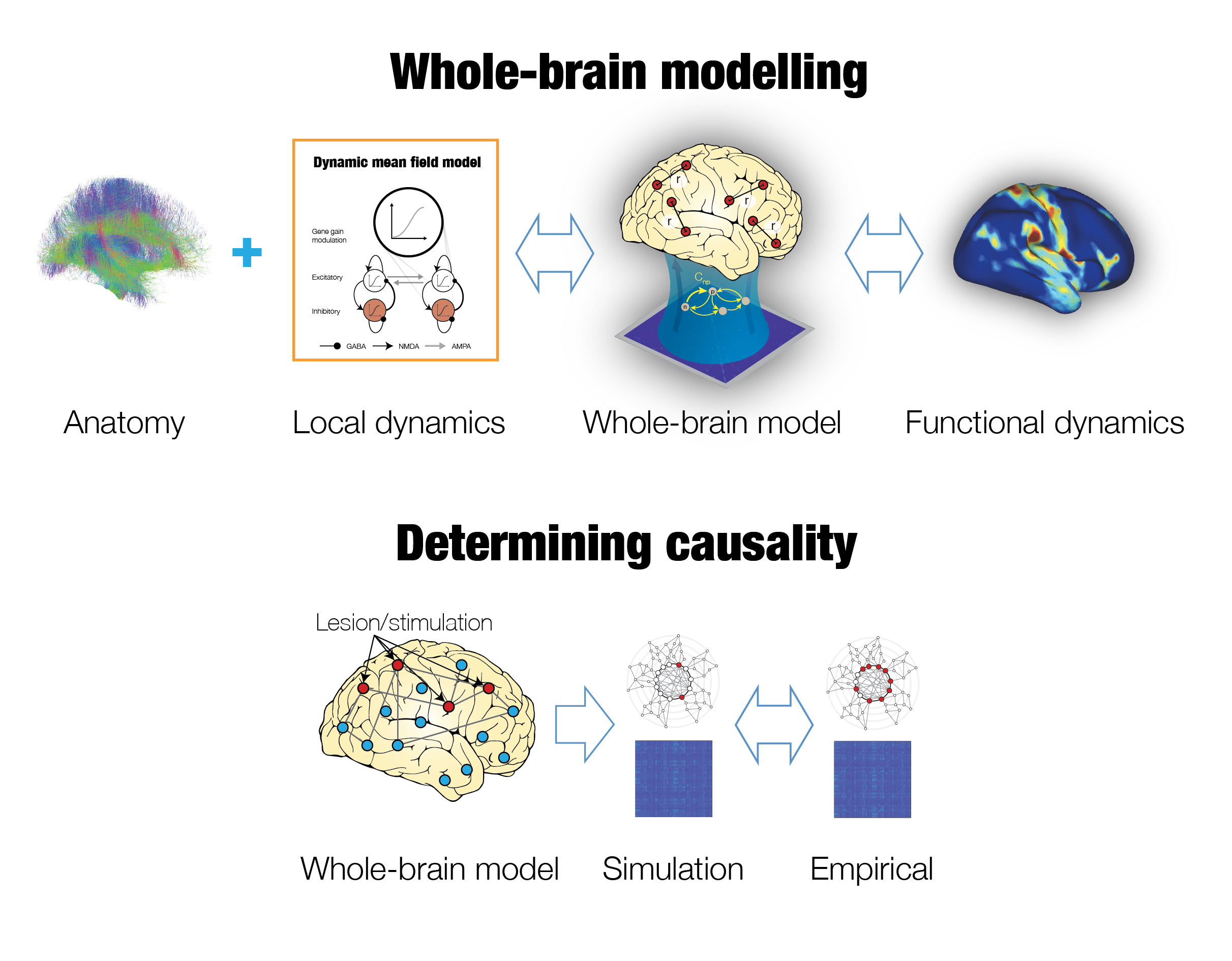

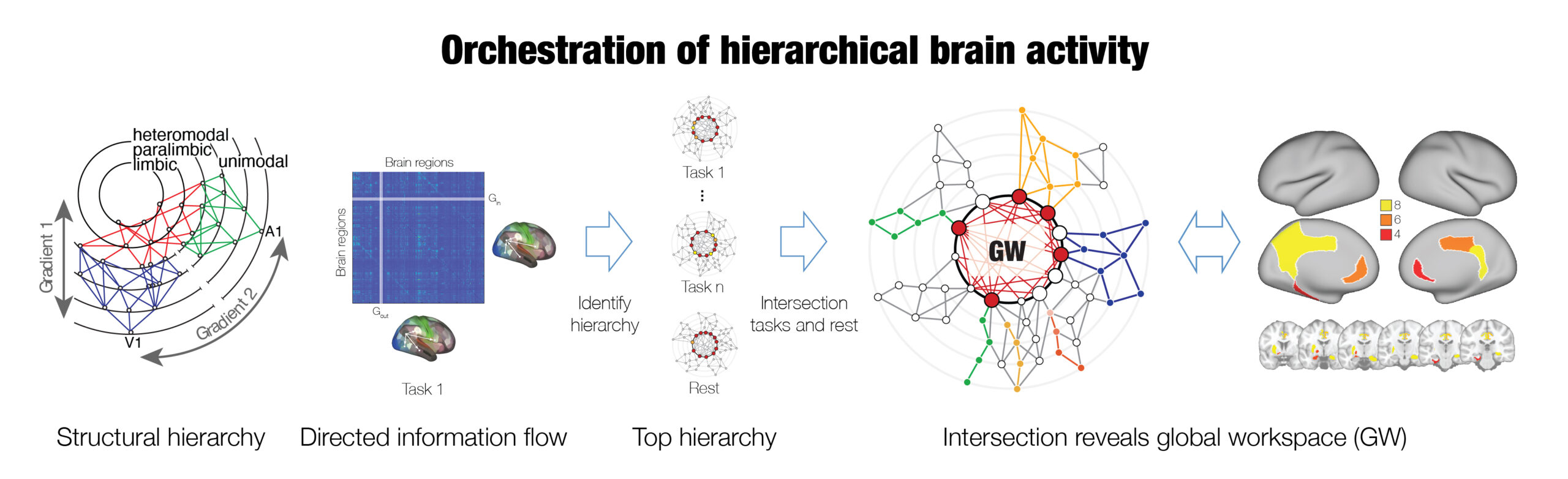

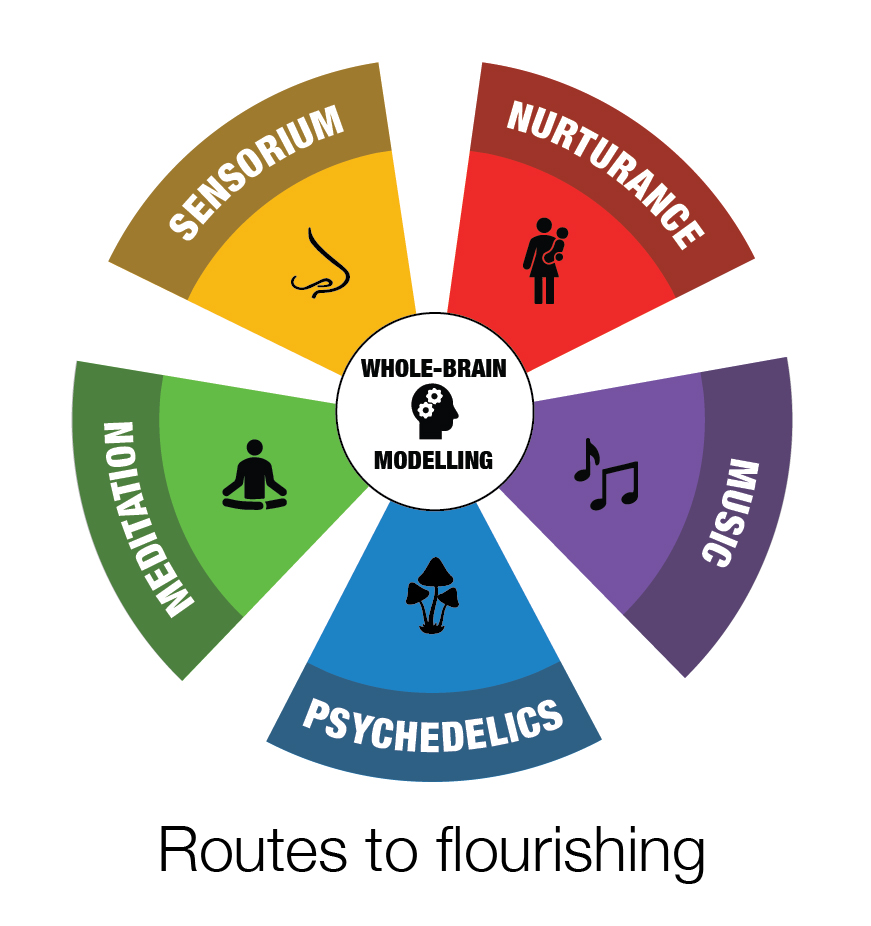

This interdisciplinary science has matured to where we may finally be reaching an understanding of some of the core principles of meaning-making and flourishing in the human brain. For example, we have now developed a fuller understanding of what goes awry in neuropsychiatric disorders: How a lack of pleasure, anhedonia, combined with a lack of motivation, avolition, cause a malignant orchestration of brain dynamics that wreak havoc on our mental health. Sophisticated causal whole-brain models have moved us significantly closer to discovering what a healthy orchestration of brain dynamics looks like, which helps facilitate finding better ways of rebalancing disease, from direct-brain stimulation, which can reduce or even eliminate chronic pain, to psychedelics, which can mitigate treatment-resistant addiction and depression.

We have spent well over two decades trying to establish an interdisciplinary science of pleasure and flourishing. We had to overcome many obstacles along the way, but establishing the Centre provides the stability and autonomy we need to make more rapid progress in our mission to help find ways to make better lives.

The many outstanding questions will require much more than just research in a centre based in a small city at the confluence of seven rivers. We have therefore established the International Centre of Flourishing that brings together our research in Oxford, Barcelona and Aarhus, conducted in the flourishing spirit of ‘nit nitay garabam’ (‘people are people’s medicine’-Wolof).

Recently, re-reading “The Log from the Sea of Cortez” by writer John Steinbeck and marine biologist Ed Ricketts, it is difficult not to despair of the “tragic miracle of consciousness” central to human existence and, as they write, our “species is not set, has not jelled, but is still in a state of becoming”. Yet, we choose to cling on to the hopeful “state of becoming” rather than worry about the unchangeable past and uncertain future. We must seek better ways of finding meaning in the now and we hope that many of you will join us in this interdisciplinary endeavour given that our very future – and that of other species and our tiny blue planet – will depend on it.

More information about the underlying science in:

Kringelbach M.L., Vuust P. & Deco G. (2024) Building a science of human pleasure, meaning-making and flourishing. Neuron, 112(9), 1392-1396.